Nazareno Lupi and his wife, whose family hid John Everett and Willis Largent for over nine months. John received this picture after the war from the Lupi family.

Nazareno Lupi and his wife, whose family hid John Everett and Willis Largent for over nine months. John received this picture after the war from the Lupi family.

John Everett (with arms crossed) and two comrades.

John Everett (with arms crossed) and two comrades.

Two weeks ago I received these photographs and the following story from John O. Everett, Jr.

He wrote, “Dad’s story is in the form of a submission he and I made to TNT years ago when they were focusing on soldiers’ stories one Memorial Day weekend. I had sat down with my Dad several times to obtain the timeline and other details for the story, and it was completed and submitted a year before he died. Although TNT did not include his story during the broadcast, I am so glad that I documented his experience so that I can provide the details to you.”

John O. Everett, Sr. passed away in 1995.

It’s a pleasure to share his story, and it’s my hope that the gratitude he wished to send to the Lupi family by way of the TNT broadcast will find it’s way to them somehow through this site.

John Everett and Willis Largent were both interned in

Hut 4–Section 11—the section of men Armie Hill was assigned when he was transferred to the camp.

Here is John’s tale, which he named “The Unsung WWII Heroes of Italy: A POW’s Story.”

The Unsung WWII Heroes of Italy:

A POW’s Story

“What the hell part of the world are you from?”

I still remember this question asked of three scruffy American soldiers in June, 1944 by an officer in the South African Army near Foggia, Italy. The rags that served as our clothing were part U.S. Army issue, part Italian farmer, and our boots had more holes than leather. And yet we were happy, we were safe, and we owed our lives to an Italian family that hid four prisoners of war from the Germans for over nine months.

The history books tell us that Italy was our enemy during World War II. But you will never convince a number of POWs who owe their lives to the courage and generosity of several poor Italian families who shared when they had nothing to give.

World War II began for me when I was drafted in early 1942. I had originally volunteered for service in 1941, but was turned down due a problem with my legs. Like so many other health problems, mine was “reevaluated” when the fighting got hot and heavy in 1942.

On August 2, 1942, I shipped out of New York harbor on

the Queen Mary with 17,000 other soldiers for service in North Africa. For a while, my service there as a private in the “Big Red One” (1st Infantry) was uneventful, highlighted only by the

opportunity to deliver a message to General George Patton. I will never forget those pearl-handled revolvers.

However, in April, 1943, Sgt. Calvin Hannah of California and I were returning by

jeep from establishing a forward command post near Kasserine Pass, North Africa. We became lost and drove right into a German machine gun nest, and were quickly surrounded by German soldiers. Having no alternative but to surrender, we were taken as prisoners of war and after two weeks were shipped to Camp P.G. 98 in Sicily. We were kept there for 28 days, and nearly starved to death. We were then shipped to Ascoli province in central Italy in May, where we were treated fairly well as POWs and even began to receive Red Cross parcels.

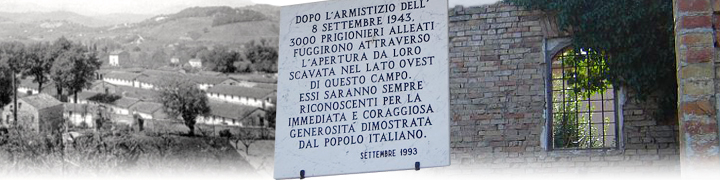

Our relatively secure existence as POWs came to a sudden halt in September, 1943. Italy had decided to pull out of the war, and the prison camp was behind the German lines to the South. The Italian camp officials told us to be patient, and that they would try to train us back to the American lines. However, the Allies had landed in Southern Italy, and the Germans were retreating towards Ascoli. Fearing that the Germans might simply kill all POWs as they retreated, the camp officials swung open the prison gates at 10:00 p.m. one night, gave us Red Cross parcels, wished us luck, and told approximately 1,200 prisoners that we were on our own.

This was the loneliest feeling that I ever had in my life. For a farm boy from Mississippi, this was scarier than anything I had ever faced. We only knew that the Allies were to the South, and that the Germans were to the North, South, East, and West.

Six of us grouped together and walked all night, stopping the next morning only after we had walked about 20 or 25 miles. And it was a good thing that we did not stop to rest; we learned later that a number of the POWs were captured that night when they chose to rest first before beginning their journey.

I ended up traveling with one other soldier, Willis Largent of Maryville, Tennessee. After about two weeks, we eventually walked up to a farmhouse near the small town of Force on a Sunday morning, where a young woman was working in the yard. After much discussion, we decided to approach her and ask her, in our broken Italian, if we could have some hot water for the instant coffee in our Red Cross packs. She called her father, Nazareno Lupi, who invited us in and asked us to stay and eat with them.

After supper, Nazareno asked us to stay in their barn until it was safer to travel. We were leery of doing this, but this seemed to be a better alternative than taking off in an unknown direction for an unknown future. This poor Italian farm family, with little to eat, ended up hiding us for over nine months from the Germans.

We tried to help out with the farm as much as we could, and we ate as little as possible because there was so little to go around. They were entirely self-sufficient; they plowed the fields with an ox, had a small vineyard, and had no electricity. Wartime was especially tough on farm families; obtaining something as simple as salt was extremely difficult.

There were two families living in the house: Nazareno, his wife and three daughters, Nazareno’s widowed sister-in-law and her three daughters, and a granddaughter Ida (who we first approached asking about hot water). Ida’s father was in the Italian Army, and the family had no idea of where he was or if he was alive.

We soon received word that two other POWs were nearby at the Marcozzi farm. The were Owen Frye of Bluefield, West Virginia, and William Helmly of Savannah, Georgia. The four of us spent much of our time together, staying close to the farms and seldom venturing out. Two of the times that I decided to venture out almost ended in disaster.

On Christmas Eve, 1943, I decided to walk to Force to see if there were any other GIs in the small town. On the way, I suddenly heard a convoy coming, and the mountain road was such that I had no place to hide. I pulled the old Italian overcoat over my face and continued to walk. Sure enough, it was a German convoy. Although they looked at me briefly, they apparently decided that I was just an Italian farmer on the way to town (albeit one who was 6’3″ tall), and they continued on their journey.

The second close call occurred in early 1943. We heard a rumor that the Allies were in San Benedetto, a town on the eastern coast of Italy approximately 20 miles from Force. Three British POWs and three of us walked to the town, and just as we were about to top a small mountain overlooking the town, someone called out to us. A small group of American and British POWs appeared and told us that the town was crawling with Germans, and when we moved forward for a closer look, we saw nothing but German soldiers, vehicles, and ships. We quickly hiked the 20 miles back to the Lupi farm that night, not bothered to stop along the way.

The Allies knew that there were a number of POWs loose on the Italian countryside, and occasionally we could hear the Allied planes fly over. Owen Frye painted the letters POW on an old door, and we would put it out in the field each day. One day we learned that the Allies had airdropped packages of food, clothing and shoes over the area for all the POWs in the hills. Unfortunately, they managed to drop them right in the middle of a group of die-hard Fascists who still supported the German soldiers. Needless to say, we never received the packages.

By June, 1944, the Allies had forced the Germans into retreating farther north. Frye and I decided to once again try to make our way south and hook up with the Allies. We walked into Force and soon heard some locals shouting that jeeps were coming. We soon discovered that it was an American convoy, and for the first time we felt that our ordeal was finally over. Our joy was tempered by the officer in charge, who told us that his group was an advance detail and they could not handle us, and that we should continue to make our way south. He assured us that it was clear south of town. We were able to hitchhike with another poor Italian farm family, who let us ride on the back of their truck that was packed with everything that they owned.

Eventually, we ran into the South African Army contingent with the puzzled officer mentioned earlier. This group fed us, and we gorged ourselves to the point of becoming sick. They gave us British Army clothing and eventually put us on a train to a British camp in Foggia, Southern Italy. They turned us over to the 8th Air Force, and after a couple of weeks we were sent on a plane back to Algiers, North Africa. Finally, we were put on a ship back to the U.S., and on August 2, 1944, exactly two years after I had shipped out of New York, we arrived in Boston.

I had no idea where my family was when I returned to the States. My mother had been told that I was missing in action, and eventually was told that I was being held as a prisoner of war. I finally found my family, got married, and spent the rest of my Army service at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, near my hometown of Hattiesburg. And in a strange twist, I spent some of the time guarding German prisoners at Camp Shelby. On December 31, 1944, the local paper mistakenly listed me as being killed in action. They subsequently printed a correction the next day, noting that a “strapping young man came by the paper’s office today and informed us that he is very much alive.”

I was able to write the Lupi family a couple of times after the war, and I learned that Nazareno had died shortly after I left. (One of the letters was interpreted for me at Camp Shelby by a German prisoner.) We soon lost touch, and I have often wondered what happened to the Lupi family. Owen Fry actually returned to Force, Italy in 1983 in order to locate the family. However, as he neared the town, the memories became too much for him, and he felt that someone or something was telling him not to go any further. He returned to West Virginia without ever trying to locate the farm.

In one of the letters from the Lupi family, I learned that after the war the U.S. government had paid the family $175 for keeping each of us during the war. We had left a letter with the family shortly before we left which identified us and told of how the family had taken us in, fed us, and hid us from the Germans for over nine months.

The sum of $175 was a lot of money for a poor Italian farm family in the 1940’s, but it could not begin to compensate them for what they did for us. They did not want to be a part of that war and, like many Italians, they resented Mussolini for dragging them into battle. They had every reason to turn us away that December morning (or turn us in to the Germans), but they chose to welcome a group of scared 20-year-olds with open arms.

History will record that the Italians simply gave up the fight when the going got tough in World War II. This assessment does not do justice to the courageous families who chose to risk their own lives and futures when they could have easily chosen not to do so. In these days of worldwide communications and cable television, I hope that somewhere there are members of the Lupi family watching TNT who can hear all of us simply say “Thank you.”

___________________________________________________________________

~His story in his own words~

The Unsung Heroes From Italy: A POW's Perspective

"What the Hell part of the world are you from"

I still remember this question asked of three scruffy American soldiers in June, 1944 by an officer in South African Army near Foggia, Italy. The rags that served as our clothing were part US Army issue and part Italian farmer and, our boots had more holes than leather. And yet we were happy, we were safe and we owe our lives to an Italian family that hid four prisoners of War from the Germans for nine months.

The history books tell us that Italy was our enemy during World War II. But you will never convince a number of POWs who owe their lives ro the courage and generosity of several poor Italian families who shared when they had nothing to give.

World War II began for me when I was drafted in early 1942. I had originally volunteered for service i 1941 but, was turned down due to a problem with my legs. Like so many other health problems, mine was "reevaluated" when the fighting got hot and heavy in 1942.

On August 2, 1942, I shipped out of New York Harbor on the Queen Mary with 17,000 other soldiers for service in North Africa. For awhile, my service there as a Private in the "Big Red One" (1st Infantry Division) was uneventful, highlighted only by the opportunity to deliver a message to General George Patton (I still remember those Pear handled revolvers!).

However, in April of 1943, Sgt Calvin Hannah of California and I were returning by jeep from establishing a forward command post near Kasarerne Pass, North Africa, We became lost and drove right into a German machine gun nest and, we were quickly surrounded by German soldiers. Having no alternative nut to surrender, we were taken prisoners of war and, after two weeks we were shipped to Camp P.G. 98 in Sicily. We were kept there for 28 days and, nearly starved to death. We were then shipped to Ascoli province in central Italy in May, where we were treated well as POWs and, even began receiving Red Cross parcels.

Our relatively secure existence as POWs came to a sudden halt in September, 1943. Italy had decided to pull out of the war and, the prison camp was behind the German Lines to the South. The camp officials initially told us to be patient, that they would try to train us back to rhe American Lines. However the Allies had landed in Southern Italy and, the Germans were retreating toward Ascoli. Fearing that the Germans might simply kill all POWs as the retreated, the camp officials swung open the prison gates at 10:00PM one night, gave us Red Cross parcels, wished us luck and, told approximately 1,200 prisoners that we were on our own.

This was the loneliest feeling that I ever had in my life. For a farm boy from Mississippi, this was scarier than anything that I had ever faced. We only knew that the Allies were to the South and, that the Germans were to the North, South, East and, West.

Six of us grouped together and walked all night, stopping the next morning only after we had walked about 20 or 25 miles. And it was a good thing

that we did not stop to rest; we learned later that a number of the POWs were captured that night when they chose to rest first before beginning their journey.

I ended up travelling with one other soldier, Willis Largent of Maryville, Tennessee. After about two weeks, we eventually walked up to a farmhouse near the small town of Force on a Sunday morning, where a young woman was working in the yard. After much discussion, we decided to approach her and, ask her, in our broken Italian, if we could have some hot water for instant coffee in our Red Cross packs. She called her Father, Nazareno Lupi, who invited us in and asked us to stay and eat with them.

After supper, Nazareno asked us to stay in their barn until it was safer to travel. We were leery of doing this, but this seemed to be a better alternative than taking off in an unknown direction for an unknown future. This poor Italian family, with little to eat, ended up hiding us for nine months from the Germans.

We tried to help out with the farm as much as we could and, we ate as little as possible because there was so little to go around. They were entirely self-sufficient; they plowed the fields with an Ox, had a small vineyard, and had no electricity. Wartime was especially tough on farm families; obtaining something as simple as salt was extremely difficult.

There were two families living in the house: Nazareno, his wife and, three daughters and, Nazareno's widowed sister-in-law, three daughters and, a granddaughter Ida (who we first approached about hot water). Ida's father was in the Italian Army and, the family had no idea of where he was or if he was alive.

We soon received word that two other POWs were nearby at the Marcozzi farm. They were Owen Feye of Bluefield, West Virginia and, William Helmly of Savannah, Georgia and, the four of us spent much of our time together. We stayed close to the farms and, seldom ventured out. Two of the times that I decided to venture out almost ended in disaster.

on Christmas Eve, 1943, I decided to walk to Force to see if there were any other GIs in the small town. On the way, I suddenly heard a convoy coming and, the mountain road was such that I had no place to hide. I pulled the old Italian overcoat over my face and, continued to walk. Sure enough, it was a German convoy. Although they looked at me briefly, they apparently decided that I was just an Italian farmer on the way to town (albeit one who was 6'2" tall) and, they continued on their journey.

The second close call occurred in early 1943. We heard a rumor that the Allies were in San Benedetto, a town on the Eastern coast of italy approximately 20 miles from Force. Three British POWs and three of us walked to the town and, when we were on a small mountain overlooking the town, someone called out to us. A small group of American and british POWs appeared and, told us that the town was crawling with Germans and, when we moved forward doe a closer look, we saw nothing but German soldiers, vehicles and, ships. We quickly hiked the 20 miles back to the Lupi farm that night, not bothering to stop along the way.The Allies knew that there were a number of POWs on the Italian Countryside and, occasionally we could hear planes flying over. Owen Frye painted the letters POW on an old door and, we would put it out in the field each day. One day we learned that the Allies had airdropped packages of food and, clothing and, shoes over the area for POWs in the area. Unfortunately, theu managed to drop them right in the middle of a group of die-hard Fascists who still supported the German soldiers! Needless to say, we never received the packages.

By June, 1944, the Allies had forced the Germans into retreating further North. frye and I decided to once again try to make our way South and hook up with the Allies. We walked into Force and soon heard some locals shouting that jeeps were coming. We soon discovered that it wa an American convoy and, for the first time we felt that our ordeal was finally over. Our joy was tempered by the Officer in charge, who told us that his group was an advance detail and they couldn't handle us and, that we should continue to make our way South. He assured us that it was clear South of town. We were able to hitchhike with another poor Italian family, who let us ride on the back of their truck that was packed with everything that they owned.

Eventually, we ran into South African contingent with the puzzled officer who asked us the question mentioned earlier. This group fed us and, we gorged ourselves to the point of becoming sick. They gave us British Army clothing and, eventually put us on a train to a British camp in Foggia, Southern Italy. They turned us over to the 8th Air Force and, after a couple of weeks we were sent on a plane back to Algiers, North Africa. Finally, we were put on a ship back to the US and, on Agust 2, 1944 (exactly two years after I had shipped out of New York) we arrived in Boston.

I had no idea where my family was when I returned to the States. My Mother had been told that I was missing in action and, eventually was told that I was being held a POW. I spent the rest of my Army service ar Camp Shelby, Mississippi, near my home of Hattiesburg. In a strange twist, I spent time guarding German POWs at Camp Shelby. On December 31, 1945. the local paper mistakenly listed me as being killed in action; they subsequently printed a correction when I appeared in their offices to assure them that I was very much alive. (Copies of the articles are attached.)

I was able to write the Lupi family a couple of times after the war and, learned that Nazareno had died shortly after I left. (One of the letters was interpreted for me at Camp Shelby by a German Prisoner) We soon lost touch and, I have often wondered what happened to the Lupi family. Owen Frye actually returned to Force, Italy about ten years ago in order to locate the family. However, as he neared the town, the memories became too much for him and, he felt that someone or something was telling him not to go any further. He returned to West Virginia without ever trying to locate the farm.

In one of the letters from the Lupi family, I learned that after the war the US Government had paid the family $175.00 for keeping each of us during the war. We had left a letter with the family shortly before we left which identified us and told of how the family had taken us in, fed us and, hid us from the Germans for over nine months.

The sum of $175.00 was a lot of money to a poor Italian farm family in the 1940s, but it could not begin to compensate them for what they did for us. They did not want to be part of that war. and like many Italians, they resented Mussolini for dragging them into the battle. They had every right to turn us away (or turn us in to the Germans), but they chose to welcome a group of scared twenty year olds with open arms.

History will record that the Italians simply gave up the fight when the going got tough in World War II. However, this assessment does not do justice to the courageous families who chose to risk their own lives and futures when they could have chosen not to. In these days of worldwide communications and cable television, I hope that somewhere there are members of the Lupi family watching TNT who can hear all of us simply saying "Thank You".

This story was shared with me by John O Everett's Granddaughter

Billie Barnett

Find the list of Names for POWs kept at Camp 59